- Home

- Photo Galleries

- Portrait Photography

- Landscape Photography

- Street Photography

- China

- Ethiopia

- India

- Holy Ganges

- Varanasi

- Varanasi Ganga Aarti

- Varanasi, Manikarnika Ghat

- Varanasi Streets & Alleys

- Varanasi Demolition

- Varanasi Fruit Market

- Sarnath

- Brick Kilns

- Tamil Nadu, Chennai & Mamallapuram

- Tamil Nadu, Fort Tirumayam & Madurai

- Tamil Nadu, Tiruvannamalai & Thanjavur

- Kerala, Munnar

- Kerala, Peryiar

- Kerala, Backwaters

- Kerala, Kochi

- Kazakhstan

- Myanmar

- Senegal

- Uzbekistan

- Travel Blog

- China

- Ethiopia

- India

- Tamil Nadu & Kerala

- Varanasi

- Whato to do in Varanasi

- Varanasi Life along the Ghats

- Varanasi Death along the Ghats

- Varanasi Ganga Aarti Ceremony

- Varanasi demolished to honor Shiva

- Varanasi Fruit Market

- “Varanasi, A Journey into the Infinite”

- Sarnath

- All about River Ganges

- Holy Shit. All about Indian Cow Dung

- Clean India Project

- Brick factories

- Tilaka, pundra, bindi: what is the mark on Indian foreheads?

- Kazakhstan

- Mongolia

- Ulaanbaatar, the coldest capital in the world

- What to do in Ulaanbaatar

- Chinggis Khan Museum, 6 floors of Mongolian history

- Gorkhi-Terelj National Park and Bodgkhan Natural Reserve

- Altai Mountains, Things to do in Olgii and Sagsai

- Living with the Eagle Hunters

- Sagsai Eagle Festival

- Navrus Festival

- Xöömej, Mongolian throat singing

- Mongolian Food

- Myanmar

- Senegal

- Uzbekistan

- Latest Posts

- Photography Blog

- About

- Prints

No other place in the world recalls the Silk Road as Samarkand. Its streets are full of myths and legends and the monuments built by Tamerlane make its atmosphere magical. Despite the recent restoration works have partially transformed its face, bringing it closer to the typical Russian town with its avenues and parks, Samarkand remains a breathtaking beauty. Registan, Gur-e-Amir, Bi-Khanym Mosque and Shah-i-Zinda are among the most spectacular monuments in Central Asia. And, if we retrace the thread of its history, we must admire its tenacity as Samarkand has been reborn several times from its ashes.

Share with your friends:

The many lives of Samarkand

“Founded in the 8th century BC, Samarkand is one of the oldest towns in Central Asia.” Malika, the guide we contacted, wastes no time and immediately gives us a little knowledge.

“When Alexander the Great conquered it in 329 BC, he said: ‘Everything I have heard about Samarkand is true, except that it is much more beautiful than I imagined’.

For centuries, the city had been a trade center along the Silk Road and here converged caravans from China, India and Persia. It remained a highly populated and commercially relevant center until 1220, when the destructive madness of Genghis Khan wiped it from the face of the earth.

Samarkand remained a pile of rubble until 1370, when Timur (Timerlane) decided to rebuild it and make it his capital. He brought in artisans and artists from all over Central Asia and they offered their knowledge to rebuild it and make it not only a commercial but also a cultural epicenter.

His nephew Ulugbek built an important astronomical observatory here, with a 30-meters-wide quadrant which is still admired.

In the sixteenth century, the city risked disappearing again. The capital of the empire was moved to Bukhara and Samarkand, after several earthquakes, was almost entirely abandoned.

It was the Soviets, at the end of 1800, who injected new life into the city, connecting it to the transcaspian railway network”. We can really say Samarkand is a tenacious city, which can stand the proof of time. It was reborn from its ashes several times. You got to love it!

Samarkand's Registan

I arrive in Samarkand after sunset, with one thing in my mind. The Registan, with its large square and imposing tiled facades. I would stop here for hours, admiring the facades of the madrassas – yet a row of barriers block my enthusiastic outbursts.

“They’re putting on a show for tomorrow night,” a policeman tells me. “There’s no access to the square at night. Singers and dancers need to rehearse”. A huge stage occupies one side of the square and there are platforms and stands on the others. My disappointment is huge. “You can visit the square in the morning,” adds the guard trying to comfort me. The stage and the stands will not disappear at dawn, nor will it be possible to delete them from my photos, I think. “All right, thank you,” I reply embittered. “Don’t worry, Andrea”, whispers Giulia to my ear. “We’ll find a way to get past those hurdles”.

We return the next morning and I understand that no barrier can put the Registan in a corner.

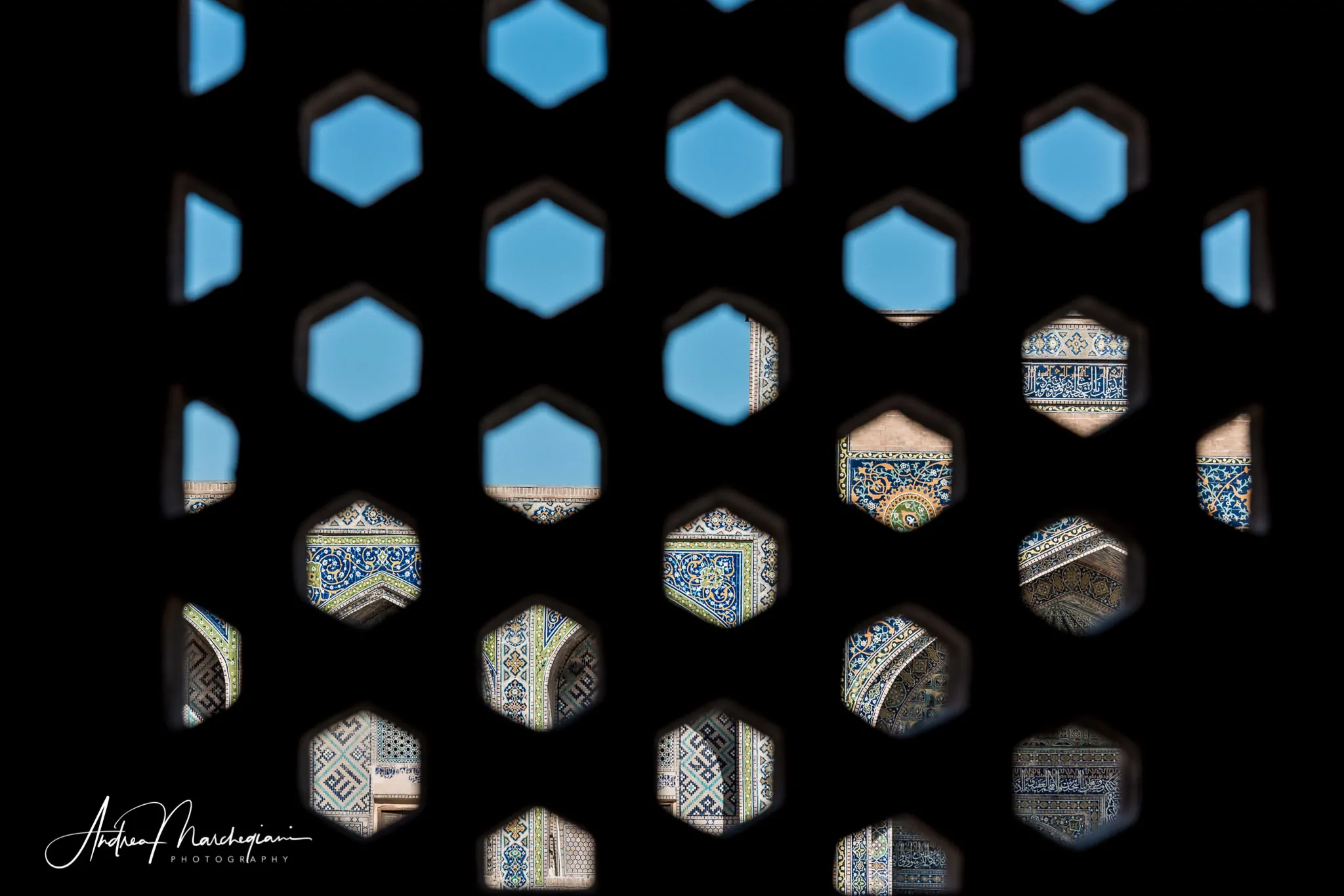

There is an almost exaggerated quantity of blue mosaics, not to mention the vastness of the spaces and the harmony with which the three madrassas relate to each other. Without a doubt, the Registan is one of the most extraordinary places in Uzbekistan. Malika has already begun her explanation. I find it hard to follow her, with so much beauty to admire.

“At the center, is the madrasa Tilla Kari, completed in 1660, which amazes for its golden interiors symbolizing the wealth of Samarkand”. The ceiling amazes me. There is so much gold it is impossible not to be bewitched.

“See the dome? It’s an optical illusion. The ceiling is actually flat, but its refined concentric patterns give the impression that it is a dome”.

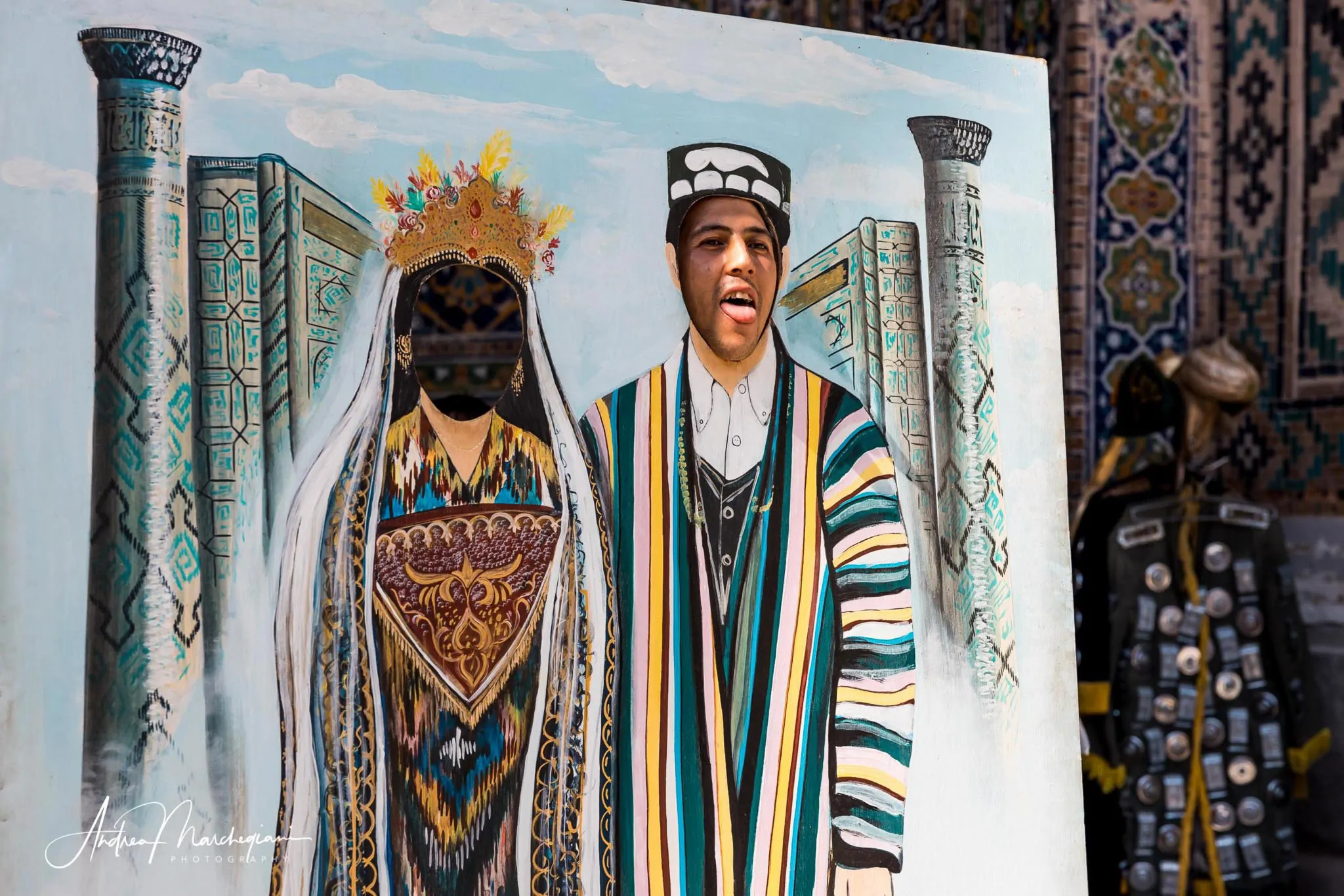

On either side of the square, the madrasa of Ulugbek and the madrasa Sher Dor face each other. The first, built in 1420, has starry motifs on the facade, testifying to Ulugbek’s deep love for astronomy. They say he taught mathematics here. The madrasa Sher Dor (madrasa of the lion), dates from 1636 and its decorations are unique. They decipt felines in the act of hunting a deer, which clearly contradict the Islamic ban on painting animals: in fact, these animals are Zoroastrian inspired. I walk away from the guide for a few minutes and wander around the inner courtyards of the madrasas. There is a relaxed and playful atmosphere. Inside Ulugbek’s madrasa of people get dressed in traditional clothes and get their picture taken just for fun. A boy with an attractive smile and a child with a warrior look give me some magic shots.

Registan from a different angle

“Andrea, run!” Giulia shouts from afar.

She’s talking to a cop, and I see them gesturing.

“This guard will let us enter the disused apartments of the madrasa!!”

It seems a unique opportunity, so I hasten to reach it. As I make my way Giulia has already entered into a small door of shabby wood. She climbs up dangerous stairs, inside a dusty and flayed entrance hall. The policeman stops me with a gesture of his hand.

“Giulia! The guard won’t let me in!” I shout from outside.

“Give him five euros!”. Give him five euros???

“Giulia! Are we bribing a policeman???”.

“Of course we are. Come on, it’s beautiful!”

I hope I don’t get in trouble again, like I did on the night train to Uzbekistan. But today is Giulia’s birthday and her cheerful voice is irresistible. I pay my due to the police officer, who comments “Be quick!”. I climb the narrow dusty stairs and walk the abandoned and dangerous corridors.

Giulia is at the end of a room, curled up to give a privileged peek at the facade of the Sher Dor madrasa. “Look! It’s so beautiful, Andrea! The view from here is otherwordly!”

The policeman whistles impatiently at us. The bribery meter went off quickly.

“I read in the guide that sometimes policemen let themselves be corrupted”, Giulia whispers. “But I swear this time I didn’t ask for it. He came to me!”

Gur-e-Amir mausoleum

A short taxi ride and we get to the Mausoleum of Gur-e-Amir. We came in early this morning, but the facade was fully backlit. In the afternoon the light conditions are much better.

Here lies Timur, along with two of his sons and two grandchildren, including Ulugbek. The building is very modest, despite the blue tiles of the dome being particularly beautiful. The reason is that Timur did not want to be buried here, but in Shakhrisabz, and he had this mausoleum built for his grandson.

However, when Timur died of pneumonia in 1405, the passes to Shakhrisabz were inaccessible due to heavy snow and so the great leader was buried here. Inside the mausoleum, you can visit the marble tombstones of Timur and his heirs. At the time of the opening of the tombs, the Soviets were able to ascertain that Timur was indeed lame in one leg and that Ulugbek had died by beheading. At the same time, they learned not to underestimate the power of a curse.

An inscription on Timur’s tomb, in fact, read: “Whoever opens this tomb will be defeated by an enemy more fearsome than me”. The next day, Hitler’s troops invaded the Soviet Union. At least that’s what the guide told us this morning. And I’m beginning to suspect that in Uzbekistan history and legends often mix to give more flavor.

Shah-i Zinda, the avenue of the mausoleums

Still on the subject of death and burials, we visit the spectacular mausoleum avenue of Shah-i Zinda. Its name means “Tomb of the Living King” and refers to the tomb of Qusam Ibn-Abbas, the first built along the avenue and dedicated to the cousin of the prophet Muhammad.

Later, Timur and Ulugbek decided to bury relatives here and decorate the mausoleums with some of the most beautiful decorations in the Muslim world. Today Shah-i Zinda is a particularly popular pilgrimage destination in Samarkand. I wander around looking for interesting views and I am not disappointed. The continuous parade of faithful and tourists along the avenue is a very effective memento mori. I don’t know if heaven exists, but I hope it has walls so beautifully decorated.

Bibi-Khanym mosque

The last stop of my visit to Samarkand is the Bibi-Khanym Mosque, which was once among the largest mosques in the Muslim world. It was built by order of Timur, who financed it with the loot stolen during the invasion of India. Its size challenged the abilities of the builders to such an extent that the dome began to fall before it was finished.

Over the centuries the work continued to deteriorate and building materials were stolen by the inhabitants of Samarkand who needed it. In 1897, it partially collapsed during an earthquake and only recently restoration work began. Malika takes on a dramatic air and unleashes yet another spicy rumor.

“Legend has it that the mosque was commissioned by Bibi-Khanym, Timur’s Chinese wife, who ordered its construction while his husband was at war. The architect, however, fell in love with her and refused to finish the work if he did not get a kiss from Bibi in return. She agreed to see the mosque finished. But the kiss was so passionate that it left a mark on Bibi’s face. The woman was forced to cover her face to hide it. On his return, Tamerlane noticed the veil on his wife’s face, asked her to remove it, and thus learned of the betrayal. Enraged, he repudiated his wife and ordered the architect killed. He also imposed the veil on all Muslim women, so that men would no longer be tempted. Like all repudiated wives, Bibi had the right to take something from home before being banished. So, she showed up in front of Tamerlano with a big empty bag. He asked her what she wanted to put in it and Bibi replied: “I want to put you in it, since you are the only thing I care about”. The king was so struck by his wife’s gesture of love that he decided to forgive her”. This is not the true ending of the legend – at least not according to my tour guide – but Malika decides to tell us this romantic and sweetened version and I’m totally fine with it!

Uzbekistan and arranged marriages

As I walk through the mosque, which still has some crumbling parts, I come across a married couple. I’ve met many in Khiva and Bukhara, too. I smile and they let me take some pictures. “In Uzbekistan”, the guide tells me, “we say a young woman is like a gazelle. When she marries, she becomes an antelope and when she has children, a cow“. “What do you mean, a cow?” I wonder, amazed. “Yes, a cow. She gets fat and lets her daughters take care of everything”. This is not a very respectful picture, and the guide should not think otherwise. “Actually married men also get fat. They drink and eat without measure!”.

In Khiva, I attended a wedding ceremony that really impressed me. The bride kept bowing to her husband, out of respect. I would have liked to see her husband bowing, too, but he didn’t. “Things are changing, especially in cities,” Malika tells me.

“Tradition wants weddings to be arranged. The mother of the future groom chooses the future bride and goes to talk to her mother. She says ‘What a beautiful garden you have! I have a woodpecker who would love to come and peck it’. If the woman accepts, the marriage is arranged.” I ask her if she is married and she answers yes. “But I refused many proposals before accepting. I chose the guy I liked!”

Siyob bazaar and the value of hospitality

Right next to the mosque there is a lively market, called Siyob Bazaar. I sneak in, trying not to make eye contact, but my camera gets a lot of attention. Traders let themselves be photographed without problems, indeed they even pose. As I have often noticed during the trip, here hospitality is a truly rooted value.

While it is good practice for Christians to share what they have with their neighbour, for Muslims it is a duty to give everything to the guest. In my case, people understood what I was looking for and offered it to me, giving their best smile for my shots. Children, teenagers, adults and the elderly just met decided to give me some of their time. And they all thanked for being photographed, holding their hands over their hearts in gratitude.

I leave this city very reluctantly. Back at the hotel, we decide to stop for a last look at the Registan. The show has begun. Breathtaking images are projected on the facades of the madrassas and the dancers are on stage. Giulia is determined to cross the barriers. She approaches the police with a big charming smile. “Hi guys! Did you know it is my birthday today? Can you give me a gift? Can I spend a few minutes watching the show up close?”. The cops look at each other, shaking their heads. “That’s not possible! I am sorry!”

“But I will never come back here to Samarkand again. Let me see the Registan one last time!”

You can tell from their looks they would love to please her, they just can’t. They call their boss and explain the reasons of this strange request. The nature of the problem we rapresent is twofold. It’s not just laws that need to be respected. It’s something that goes far beyond that: it’s hospitality to a foreigner.

The choice shall be made unanimously. Welcoming smiles are painted on their faces as Giulia and I are accompanied on the other side of the barriers, among the guests of honor.

“Andrea, isn’t it wonderful? What a lovely birthday present!”

We are in the heart of the Registan Square, which is the heart of Uzbekistan. And with our hands on our chests, we thank the cops for making us feel so welcome.